PROMPT

Use scientific research on happiness to transform a terrible customer experience (e.g. airport baggage claim) into a great one. Instead, my team and I challenged ourselves to make a happy experience even happier: we proposed improving the already-outstanding visitor experience at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

METHODS

Ethnography, Frameworking, Research

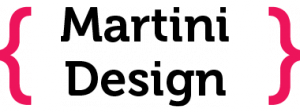

The team's first step was to spend an afternoon observing and documenting the timeline of how a visitor experience unfolds. While there, we gathered a number of stories from various stakeholders. These stories gave us insight into the different reasons stakeholders already participate in the museum ecosystem, as well as the pain points they currently experience.

FRAMEWORK

Through documenting who interacts with whom at the museum, we realized that the Cantor's identity is very much that of an institution focused on exhibiting artwork. While this may come as no surprise to you -- an art museum focused on art! -- we thought a world-class institution like Stanford deserved better for its museum.

The current museum can be visualized as follows:

Through several ad hoc interviews with guests and staff, we discovered that many visitors came to museums simply because they felt they "should." Although certainly able to appreciate the artwork, visitors often leave wanting to know more about the works:

- Why did the artist make it?

- Why is it special enough to be at a museum?

- What are they supposed to be thinking as they look at the art?

These questions should come as no surprise. Most museums put myriad barriers, both physical and psychological, between the art and the visitors, often out of necessity. Art is frequently locked in a transparent acrylic box mounted on a pedestal. The only information we're given comes in the form of a small placard, aptly called a "tombstone" that presents a few lines of predominately biographical information about the object and/or artist.

The most common request visitors had was: "I wish I knew the artist's own story behind the object." The museum staff, who possess immense subject and cultural knowledge, and are the ones who know why the object was special enough to be there in the first place, have little opportunity to share the information they know directly with visitors. Consequently, all the knowledge and enthusiasm remains behind glass, on a pedestal. Meanwhile, the museum staff sit in their offices wanting to share their passion for these objects.

Our mission at this point became clear. We needed to re-align the staff's mentality and, to some degree, organizational structure to bridge the gap between visitor and curator. We needed a shift in purpose from exhibition to engagement. We proposed re-framing the museum-workers' roles as creating a magical visitor experience using artwork as a vector. The underlying mindset influences everything from how the museum staff perform their work, where money is spent, and even what types of fonts the museum chooses to use for its brochures.

By re-framing the museum's purpose from pure exhibition of artwork to the engagement of visitors in an immersive experience, the museum structure would change to look like this:

This all sounds great in abstract, but what does this actually look like? And how do we use happiness research to guide the design of the experience?

EXPERIENCE RE-DESIGN

The team used the stories we gathered during our visit to inspire possible interventions. Each story inspired a cluster of possible interventions, all mapped to a specific area of happiness research.

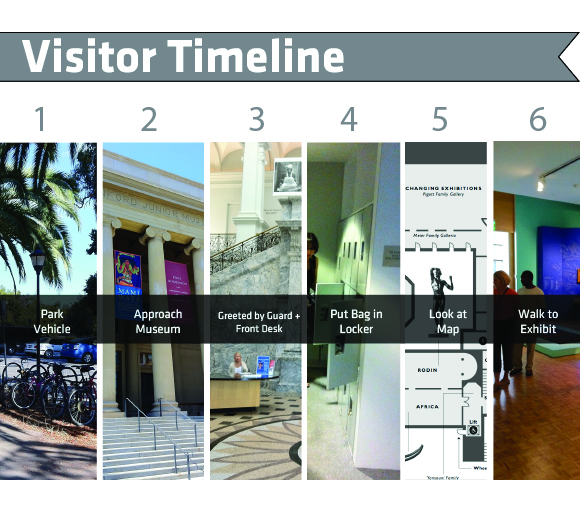

The first person we encountered was Hillary, who greets folks as they enter. Since the Cantor is free to all visitors, Hillary's main role is to help people navigate the museum. She also directs backpack-wearing visitors like us to store our bags in museum-provided lockers.

Often a visitor's first human contact at the museum, Hillary’s role is a vital and overlooked one. Research shows that anticipation plays a vital role in our happiness. In fact, anticipation for an event can be even more enjoyable than the experience itself! In addition to making suggestions to give visitors a jumping off point, she can "prime" them with questions such as, “What are you excited to see today?” This simple question reminds visitors that they are, indeed, excited to be visiting the museum and gets them started off in the right frame of mind.

Visitor motivations varies greatly, even within such a specific institutions as museums. While wandering through the galleries, we happened upon Cantor regulars, Daphne and her son. Daphne described the museum as a place where her son enjoyed playing and running around. Although a somewhat unexpected use of the space, this was a good illustration of research that has found that a person's definition of happiness changes over time: While children find happiness in simple, active activities, as we age, we find increasing satisfaction in calmer, reflective activities.

As we thought about designing for visitor happiness, we brainstormed offerings targeted at different age groups. For example, educational experiences through play are great for children, whereas young adults enjoy social events and older adults might enjoy having a meditation session in the museum's quiet, light-filled spaces.

The next stakeholder we encountered was La Trish, the head security guard. She communicated to us the joy she finds in connecting with the visitors. This was an important reminder that literally everyone in the museum has a direct impact on visitor experience, and one's best ambassadors may be wearing an unexpected uniform.

Clearly, employee motivation needs to be better understood in order to deliver a truly great visitor experience. We knew from class research that Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose are critical components of employee satisfaction. In what ways might we imbue museum jobs with these elements to let employees thrive? Our ideas were as simple as having staff being able to denote their favorite pieces of artwork to visitors, or having one-day job swaps amongst employees to help them better understand where their role fits in the larger museum ecosystem.

La Trish was not the only staff member we chatted with. Next, we ran into curator Bernard who was kind enough to let us speak with an alumnus in the process of donating a piece of artwork. This was a part of the ecosystem we had not even considered, and a good reminder of the greater systems at play in all human organizations.

The donation process highlights another source of happiness: the feelings of contentment that come from prosocial behavior like donating one's time or resources. Clearly, the museum can create a happier experience by facilitating prosocial behavior. For example, many museum visitors are incredibly knowledgeable about art and art history, or at the very least are interested in having deep discussions about the artwork. Why not have the museum facilitate impromptu meetups to allow visitors to share their knowledge and interests with each other?

As we continued to wander the galleries on that sunny day, we realized how empty they were becoming. Where had everyone gone? It didn't take us long to find out.

We discovered many visitors felt sheepish about coming to an art museum only to end up in the cafe. Food, however, is an important contributor to happiness - who hasn't felt immensely happier after being hungry and stopping for a bite to eat? The Cantor, we realized, could improve happiness by bringing the museum into the dining experience, making it a much less abrupt transition for visitors between eating and the rest of their time.

While you can't bring food into the exhibition halls (a rule we later confirmed by having our prototype intervention of a cookie platter banned from the welcome desk!) why not bring the exhibition into the dining area through themed food? For example, take a break from a French Impressionist exhibition affords you the chance to mull over your experience while enjoying a nice baguette sandwich and a glass fo wine.

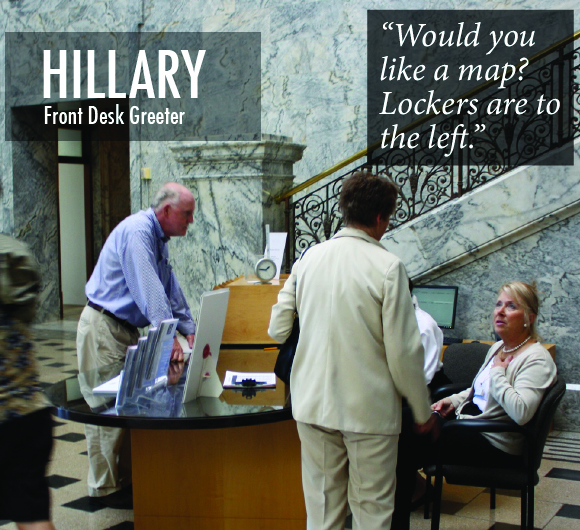

Like most visitors, our final shop was the gift shop. Nancy, the cashier, informed us that it was a well-trafficked part of the Cantor. She also gave us the insight that "Everybody wants to take some part of the exhibition home."

Since much of an event's happiness comes from when we remember it (trips to Disney World, anyone?) it makes sense to want a souvenir to aid in this remembering. It is important that the museum visit end on a high note, because research has shown the first and last moments of an event exert the greatest influence on our memory of an experience. Designers, therefore, should take advantage of this memory bias and pay special attention to those times. While the Cantor has little control over the terrible parking situation on Stanford's campus, they can incorporate creative final moments like a personalized visit book or gifts for frequent visitors during the last moments of the visit.

While this exploration was purely academic, it laid the groundwork for an actual exhibition that teammate Michael Turri and I created for our masters thesis project. We found, as many companies do, that there is huge ROI for organizations that invest in creating happy moments for their customers and employees. Often these investments come in the little details like priming visitors by greeting them with "What are you excited to see today?" that require little to no money or time.

See below for the full presentation in its original format:

(if you don't see anything, try reloading the page or visiting this link)

COLLABORATORS:

,

Mason, Oxendine, Perez-Borges