I don't think I know anyone who hasn't been bored in a museum at some point. They can be cold and sterile, and too many hours of staring at the wall makes your neck hurt. While some of this is caused by poor curatorial decisions and an insular art community that doesn't mind when outsiders feel stupid, many exhibitions actually make a valiant attempt to engage visitors, but fall short. It turns out, exhibitions that tell a good story and engage everyone from your mom to your ten-year-old neighbor are surprisingly difficult (and expensive!) to put together. Fellow d.School student Michael Turri and I spent 18 months developing an exhibition of our own while students at Stanford. Because we didn't have any clue what we were doing and had to fumble our way through creating a student-run exhibition, I wanted to create a resource for anyone else out there crazy enough to attempt one. Below are the steps we took to produce a successful event on a shoestring budget.

Step 1: Find a topic you're passionate about

Designing an exhibition takes For. Ev. Er. Seriously. So you're going to be putting a lot of hours into learning about this topic and figuring out the best way to share that knowledge with others. Take some time to make sure you and everyone else involved with the project really like the materials you'll be showing and the story that goes along with them.

In our case, this was the easy part. Michael had an obsession knack for eBay bidding that had left him with unreasonable quantities of the Eames communication design pieces they created for IBM in the 1960s-70s -- posters, videos, books, and much more. We extended our research to visting John and Marilyn Neuhart to hear firsthand what it was like to work in the Eames Design Office. We were fascinated by the parallels between the work the Eameses did to de-mystify computers during the era of mainframe computing and the work tech companies do explaining their products - Google searches? DNA testing? - to audiences unfamiliar with their product.

Here you can see Michael documenting the Neuharts' binders full of photos of the Eames' work for IBM.

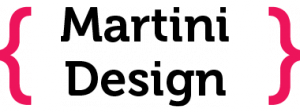

There were thousands of photos, including this one from a mockup of the famous Mathematica exhibit.

Step 2: Make sure you can afford an exhibition

We created a proposal for our exhibition, and secured a $15,000 grand from SiCa, the Stanford Institute for Creativity and the Arts. When Michael met with Cara McCarty, Curatorial Director at the Cooper Hewitt (the Smithsonian's National Design Museum) to get advice, she just about laughed him out of the room when she heard how small our budget was. But fortunately, with her help as well as the support of Stanford's Cantor Arts Center and the IBM archives, we were able to stretch this funding to cover both our exhibition and one-day symposium.

What did we spend this money on? While we were lucky to have free places to hold the symposium and exhibition (being a student is the best!) we still had to pay for:

- Food and drinks for the exhibition opening and the symposium

- A/V support for the symposium

- Foam core for displaying artifacts, some of it archival quality

- Raw materials for the wooden display cases

- Acrylic covers for the top (custom-made to spec)

- Hanging system for photos (definitely a good investment!)

- Printing posters and booklets

- Vinyl lettering for the exhibition wall

- Tickets for various museums to research exhibitions

- Website domain and hosting

- Airline tickets and hotels for speakers at the symposium

- Speaker honoraria

- A videographer

Step 3: Figure out the story you want to tell

Without a narrative to tie everything together, an exhibition can feel like it's just a lot of stuff in display cases. Given our location in Silicon Valley, it was important to us to make Eames X IBM relevant to our local audience, so we chose to tell the story of how the Eames work for IBM parallels the current-day work of designers in the technology industry. We titled the exhibit 'Eames X IBM: Communicating Technology', and focused on how design was used to introduce the general public to the complex new technology of computers.

Step 4: Needfind yourself some insights

We spent quite a bit of time stalking visitors at existing museums - SFMOMA, the DeYoung, the California Academy of Sciences and the Cantor Arts Center. After these observations and a few interviews, we had a number of insights into what was broken about the museum-going experience. Including:

Museums stink at storytelling.

People are great at storytelling.

People love to share their experiences.

Using these insights, we came up with something called a Point of View (POV), in the standard d.School form of [USER][NEED][INSIGHT]. Over the course of our 18 months we created a number of different points of view, each of which acted as a hypothesis we could prove or disprove with a round of prototyping. Here is an example of one of our POVs:

Visitors with only one hour to spend need new ways of navigating museums in order to feel confident that they’ve seen something great.

Step 5: Apply some science to your insights

Michael and I used a class at the Stanford Business School (GSB) as an excuse to look at the museum experience through the lens of positive psychology. Check out this post for a full description of that project.

Step 6: Recruit an A-team to make it happen

We put together an this video and showed it at a d.School recruiting event.

At this event, Michael and I were able to add two journalists - Chrissy Farr and Priyanka Sharma - and law student Tony Lai to our team. They brought needed energy and bandwidth to the team, which we needed for the hard work of prototyping solutions during Stanford's spring quarter.

Step 7: Prototype a bunch of ideas & fail sooner rather than later

Our team started spending a tradition of "Prototype Fridays" at the Cantor Arts Center. Through this weekly exercise we discovered a number of insights (e.g. people want to use iPhones to learn more about art, but don't want to use iPads to watch videos, since that doesn't feel like they're engaging with the museum).

One of our initial prototypes tested whether people were interested in using Twitter to interact while at a museum. We went to SFMOMA and accosted visitors on their way in, asking them to tweet @artmixer. We handed out Post-its to remind them (left), and even left Post-its around the museum surreptitiously (right).

We then stationed someone in their cafe with a laptop, ready to answer any questions people had. Unfortunately, this attempt was a resounding failure. We realized that taking out one's phone at a museum to tweet was a bit taboo. However, we didn't give up on phones entirely; later prototypes found a more compelling way to convince people to take their phones out of their pockets at a museum.

Moving away from digital for a bit, we tried out good ole-fashioned handouts. Trying to see if our POV was correct - "Visitors with only one hour to spend need new ways of navigating museums in order to feel confident that they’ve seen something great." - we created three different mini tours of the museum: The Head Curator's Favorites; the Most Popular Pieces; and the Most Overlooked Pieces. The handouts included a map, and intentionally led visitors to different corners of the museum so they could feel confident they hadn't missed anything too important.

These prototypes were extremely well-received, and we ended up doing a similar guide in our final exhibition. Below, you can see one of the visitors who followed the guide to an African Memory Board, the ancient equivalent of an iPhone.

Another failed prototype was a set of videos we created with the head curator describing various pieces of art. Below is one where she is describing a Rodin statue. We quickly discovered that visitors don't like spending their time at museums looking at an iPad screen. As one visitor said: "if I wanted to look at a screen the whole time, I would have stayed at home." Our takeaway was that any digitally-mediated interaction (tablet, phone, etc.) needed to be more active than just a canned video.

Here we tried to get feedback from visitors and discovered that it is not effective to intercept people on their way out. Once people have made up their mind to leave, they're not interested in reflecting on their visit.

Here we test a prototype of an "app": we had visitors take a photo of a sculpture. A minute later, they received a text with a "tidbit" of information about that piece, giving them a toehold for interaction. For example, a tidbit about this sculture would be that all three men are identical, just posed at different angles. The response to this prototype was resoundingly positive, and made us confident that we could meaningfully integrate an app into a museum exhibit.

During these visits, it came in handy to have journalists on the team to help record the reactions of visitors.

Step 8: Build like crazy

After dozens of prototypes, we had a good sense of what we wanted to do with our final exhibition. It then just came down to execution. Thanks to the generosity of John Edson at LUNAR, we had prime real estate in Downtown Palo Alto, CA.

This is the lobby before we touched it.

We didn't have the money to buy stands, so we had to create them ourselves.

We created and assembled the stands ourselves, but paid a professional to build the acrylic covers needed to protect the pieces on display.

A lot of planning goes into the layout of the space and the order visitors will encounter the information. Below is the tool the Cantor Arts Center uses to plan their exhibitions.

Here is Michael contemplating what photos we wanted to display for the IBM World's Fair Pavilion portion of the exhibition. We had hundreds of posters, magazines, books, photos and more to chose from, so it was quite a task to select the most important pieces to display. We narrowed in on what was important by adhering to our main story - design used to communicate new technologies - and just picked our favorite items when it came to making the final cut.

Step 9: Invite important (and relevant) people to participate

To kick off the exhibit's opening, we held an afternoon symposium to bring the content to life. We invited Eames Demetrios, grandson of Charles Eames, David Kelley and the Alex Bochannek, head curator at the Computer History Museum, among other design and tech luminaries, to speak on everything from the Eames Design Office to running a leading design firm to curating an exhibition.

Step 10: When in doubt, make an app

Being in Silicon Valley, it would be crazy not to include an app as part of the exhibition. We worked with digital design firm BuzaMoto to create SpaceMixer, an app that allowed visitors to research more about a particular item during the exhibit, rather than waiting until they were home and doing a search on Google.

Here's the app scanning a QR code to learn more about this deck of Computer House of Cards, a rare souvenir from the IBM Pavilion at the 1970's World's Fair.

The app also had a mode that let users take photos of the event. Those photos were automatically uploaded to the SpaceMixer webpage that showed user those photos of the exhibition in realtime.

Step 11: Document the final event

The morning the exhibition went up, people wandered in thinking that a new shop had opened up. #win

Here is a photo of everyone's favorite part of the exhibit: a bona fide IBM Selectric. Hat tip to IBM for the giant poster of their design history, on display behind the amazing furniture Herman Miller loaned us. Corporate handouts are a great way to stretch limited budgets!

The entrance to the exhibition. I designed the exhibition "Playbills" sitting on the front table.

Quite a transformation from the before photo, right?

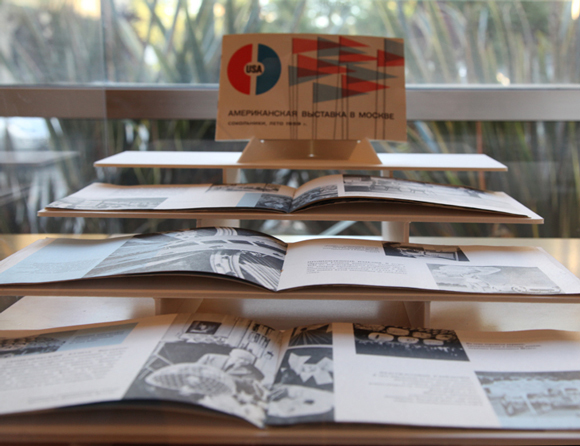

We hand-built all of the display stands out of acid free, archival foam core. This one was my personal favorite, and displays four copies of the same brochure: The American Exhibition in Moscow. This event was best remembered for the famous "Kitchen Debate" between Nixon and Khrushchev.

Step 12: Reflect

Overall, it was an exhausting yet incredibly rewarding experience. Working as a product designer in Silicon Valley, I can only hope some of the Eames' insight into communicating new technologies rubbed off on me during the course of this experience.

Special thanks to: Richard Kosoglow for assistance in building, Patience Young and Kristen Olsen for their infinite patience, and everyone else who lent us their time along the way!